|

|

DESIGNER DIARY

by Rick Heli I thought it might be fun to write something about my game design projects, something I've never tried before. |

March 20, 2021

Well, apologies that it has been super long since last time. There have

been intervening health and other matters, but happily some progress has

occurred and there are developments to talk about.

Admiral Zheng He

Founding Fathers

There are actually three developments for this game.

Imperial Glory

This is an entirely new design that began when a post by Michael Connor on

ConSimWorld asked a good question:

why haven't there been more games using the brilliant

SPI Empires of the Middle Ages system (by Jim Dunnigan and

Anthony Buccini). Michael has been subsequently working

on such a game set in the Japanese feudal system. For me, it inspired a

solution to a problem I had been pondering.

For a long time I've been thinking about how best to represent the First Four Empires period, a term I use for the ancient period 50-220 CE. Remarkably, during that time four great empires ruled Eurasia in a period of relative peace and stability, until it all came crashing down. Then it resumed once again with the Byzantine, Sassanid, Hephthalite and Tang empires, until this too came crashing down. How was it that there always seemed to be either stability or instability in all four spheres? Certainly interesting questions to study and ponder. But where to start?

Reading Michael's question it occurred to me that Empires of the Middle Ages might be a great starting point. As I reviewed it, I found some basic things I wanted to add:

Emperors

In thinking about emperors and their ratings, a problem arose. Instead

of generating random emperors, I wanted to use historical ones with

real names, ratings and images. The randomness comes from the order

in which they appear. But some of the

Roman emperors who today are considered bad were not necessarily

incompetent. It would be more accurate to say that they had different interests.

Nero considered himself first an artiste. Caligula was more interested in

practical jokes. These are just two examples. What could be a good way to

rate such emperors?

Advisors

I decided simple ratings were just not enough. Somehow the design should

reflect their whimsicality. The solution was to add advisor cards for each

emperor. That way, the more an emperor is interested in war (Trajan), the

economy, diplomacy, architecture (Hadrian), art (Nero), philosophy (Aurelius)

or subterfuge (Caligula), the more cards of this type their deck will have.

Each turn then, from your hand of five, you will turn up one, which tends

to be one of his favorites. If the player, as the emperor's consigliere,

doesn't want to perform the corresponding action just now, they can spend

an influence point to draw another card, in effect to see whether they

can change the emperor's mind. It's not only a push-your-luck system,

it also requires evaluation of just how serious the current

situation and how necessary taking a different action really is.

Deck Size

If your action succeeds, you get to add an advisor to your deck, but

if you fail, you lose the advisor(s) you used. In addition, when you

conquer an area you add the corresponding province card to your deck.

You can also use the subterfuge action to remove an advisor.

In these ways you have some control over the size of your deck.

At times you may prefer a fat deck to have more options and

keep costs lower – when

your deck exhausts you must pay to maintain your armies – but on

the other hand a thin deck brings back your best advisors

and generates trade income more quickly.

Influence

On top of this, the player needs to succeed in whatever action they choose

if they want to keep their spent influence points. Failing, or spending

too much, will limit your ability to convince the emperor to your way of

thinking in the future. More influence appears when the emperor dies, the

amount depending on his popularity at that time. So if you did well by the

previous emperor, the new one will pay more attention to you.

Armies

The original game didn't feature armies. Instead, combat is essentially

a comparison between the economic level of the origin province with that

of the target, plus leadership and money. One way to make this more

interesting is to place actual armies on the map, but then, how should

they fight? This was the biggest stumbling block in the design. Such a

subsystem could become extremely detailed. After all, there are entire

games whose raison d'être is an ancient battle.

But it was important that it not become too

long or involved lest it overshadow the rest of the game. On the other

hand, it could be very simple, perhaps simply comparing the number of

armies and their types and maybe adding some cards and dice to reach a

resolution. But this would run the risk of being so abstract as to be

dissatisfying.

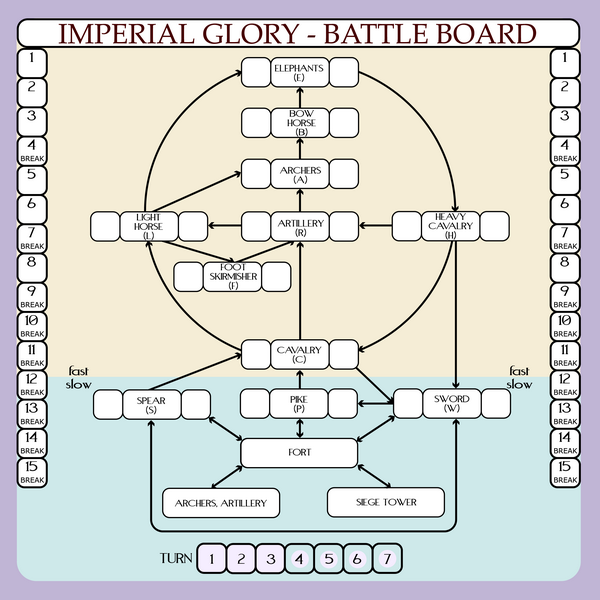

Combat

So what to do? After a lot of pondering and going back and forth between

various ideas, I happened upon a schematic chart to study ancient combat that

I made a long time ago. It depicts relationships between various types of

ancient units, the same kinds of units featured in this game. Could this

chart somehow serve as a basis for a combat system?

Terrain

In the original game all provinces were generic, but now that we were

venturing outside Europe it seemed important to represent variety in this

area. In particular, the Kushan forces were primarily horse archers. While

this was a very powerful type of unit, it definitely had limitations in

the forests and deserts. I not only assigned each province a terrain type,

I also assigned types to the connections between provinces to reflect

mountain passes that hinder movement.

Trade

Trade is often difficult to represent well when the players represent

governments. Governments can encourage or inhibit traders, but fundamentally

trade is an activity that occurs independent of their activities. Thus,

it's better for trade to operate autonomously within a governmental system

rather than let the players make its decisions. Given that, the problem was

how to represent it usefully without going into too much detail. At length

I decided that since players already had decks that they traverse,

these could

be good venues for the periodic arrival of trade. Each empire has a trade

card that, when drawn, they pass to the discard pile of the

next player on the route. Then when the next player draws it out of their

deck, they receive the trade income and pass it to the next player.

Fighting the System

One of the most fun aspects of the original game is that you spend a lot

of time fighting the game system, in some scenarios more so than the other

players. I wanted to keep this concept, but avoid all the special tables

and phases that the original has. Instead, I decided to funnel all this

type of activity into a single phase, the draw of the Fate card, which can

trigger all kinds of civil wars, coups, heresies and many more. I placed

this at the end of the turn so that this surprise would take effect at

the end of the player turn. While the others are taking their turns,

the affected player can be thinking about how best to handle the new

situation, which should help keep the game moving.

Large Empire vs. Small Empire

Conceptually, a small empire should be easier to manage than a large one,

and this game certainly features wide disparities in this regard. The Kushans

begin with a single province while the Romans have almost everything we think

of when we remember the empire (not Dacia and some provinces in the east).

To model the management problem, I put the provinces on cards that live in

the player's deck. Their appearance means that their tax payments

have arrived, as well as any recruits you request of them. The third

connection, though, is with the Fate card disasters, many of which can

only affect a province in the current hand. Thus, at the start the Romans

will have a lot more places to worry about and problems to fix than the

Kushans will, even if they are receiving more income.

Results

The original game used cards to determine a result for all endeavors and

I decided to honor that, even though I could have used dice instead (and

you can still can, if you really prefer that). Originally I used result

cards, like the original, but over time it seemed the extra calamities

and benefits that these cards could provide, were too noisy. The player

is so interested in the main result that side effects are too distracting.

It turned out that people were even forgetting to implement them. I found

it better to keep such events to the Fate cards. Removing the extra effect

texts meant that the cards could become counters instead, which has advantages:

(1) it's easier to draw from a cup than to shuffle cards, (2) laying out drawn

counters takes less space. But why this and not dice? Because once some chits

are out, you have a greater idea of the likelihood of success, though not

perfectly, because the last five counters are hidden and not used. In the

ancient world they believed in taking the auspices; in this game, checking

out the counter history is the equivalent.

Pandemic

Once Trade was working, the pandemic, which moved around Eurasia via trade,

was easy to figure out. It could arise as a Fate card and

travel from player to player in just the

same way, followed by an immunity card, which would slowly end the pandemic

effects around the board.

Winning

In the original game the player with the best developed, claimed,

colonized and converted wins. This design, because of the period,

doesn't have claims, colonization or conversion, but there was

a lot of art, architecture and science. Consequently, these are

additional factors that can contribute to victory, and also permit

varying approaches to play.

Staging

Altogether this is a large game, a three-mapper stretching from Spain

to Shanghai, with lots of bits and cards. So, it seems best to just

start with one map with most of the basic stuff and add expansions

later, being mainly cards and army counters. Deciding which empires to

present was an interesting decision. The Romans and Parthians are the

most familiar. Han Dynasty China has the biggest challenge from

"barbarians". But the Kushans have a very challenging growth curve,

starting with a single province and wanting to grow in several

directions. Which order and directions to go make for such a good decision

space that you don't even miss that there are no other players. Plus,

the Kushans are probably the least familiar of the empires so there's

a chance to learn something new as well.